John Forbes' Wilderness Campaign

Setting astride his horse amid the ruins of Fort Duquesne, Colonel George Washington braced himself against the cold November air.

Context

Context

The mercury had dipped to a bone-chilling sixteen degrees and many of the soldiers in John Forbes’ army were without stockings, shoes, coats, or adequate provisions. Nonetheless, for Washington it was a satisfying experience to finally see the Union Jack planted at the Forks of the Ohio. For more than four years the young Virginian had set his sights upon seizing the coveted confluence from the French. His first attempt in 1754 had ended in a humiliating defeat and surrender at Fort Necessity. The following year, Washington accompanied General Braddock and his proud British army as they tried to expel the enemy from the region. This attempt also resulted in disaster when the French and their Indian allies crushed Braddock’s force at the Battle of the Monongahela. During the fight, the haughty General Braddock was mortally wounded and nearly nine hundred of his men were either killed or wounded. Washington himself barely escaped death as musket balls ripped through his hat and coat.

Following Braddock’s defeat, the British army retired from the frontier leaving the various provinces to fend for themselves.

For three years Washington and other provincial officers tried in vain to protect the exposed settlers living in the backcountry from the ravages of Indian war parties. Hundreds of people living on the Pennsylvania frontier fled in terror as roving bands of Indians burned homes, destroyed crops, and seized countless numbers of captives. One group of stalwart pioneers petitioned Governor Robert Morris, writing:

“The terror of which has drove away almost all these back inhabitants except us… with a few more who are willing to stay and endeavor to defend our land; but as we are not able of ourselves to defend it for want of Guns and Ammunition, and but few in number, so that, without assistance we must fly and leave the Country at the mercy of the Enemy.”

Despite such heart-wrenching appeals, the provincial assembly offered no relief as it squabbled with the governor over who should bear the costs of military appropriations. Angry settlers arrived in Philadelphia in the fall of 1755 carrying with them the disfigured bodies of their neighbors who had been killed during the raids. A large mob surrounded the government building, depositing the mangled corpses in the doorway and demanding that the assembly take action.

Finally, in November the government passed a military appropriations act which called for the recruitment of provincial troops and the construction of a chain of forts to protect the frontier. These measures proved ineffective, however, as the Indian war parties avoided contact with Pennsylvania soldiers and bypassed the forts during their raiding activities.

The Plan

John Forbes' Plan

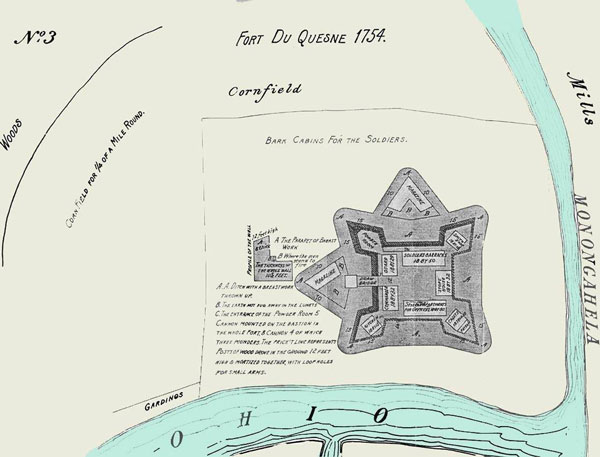

It was not until the spring of 1758 that any relief for the beleaguered settlers arrived. A new initiative, designed to defeat the French and their Indian allies once and for all, had been developed by British officials under the leadership of the new Secretary of State, William Pitt. This plan called for a new campaign, led by Brigadier General John Forbes, to be launched against the French stronghold at Fort Duquesne. General Forbes, a career soldier from Scotland, arrived in Philadelphia in April and set about organizing his expedition. The general’s plan involved cutting a road over the mountains that would lead to Fort Duquesne. Unlike Braddock, Forbes intended to pause at intervals along the march and construct forts that could be used for defensive purposes should his army be overwhelmed. These forts could also be used as supply depots and serve to protect the line of communication from the frontier to Philadelphia.

To execute his plans, General Forbes assembled a mixed force of provincial troops and regular British soldiers. This army, much larger than Braddock’s, included colonial forces from Pennsylvania, Virginia, Delaware, Maryland and North Carolina. Initially, General Forbes had little regard for the colonial troops under his command, referring to them as “an extream bad Collection of broken Innkeepers, Horse Jockeys, & Indian traders.” By the end of this long campaign, the general’s attitude toward these provincial soldiers changed dramatically.

The regular forces in Forbes’s army were made up of Scottish troops from the 77th Regiment of Foot, better known as Montgomery’s Highlanders, and four companies of the 60th Regiment, also known as the Royal Americans. This regiment included many men who were recruited among the Germans living in Pennsylvania. Also, the army consisted of hundreds of teamsters to drive the supply wagons and herdsmen to prod the sheep, cattle, and other livestock. Finally, a number of women accompanied the expedition serving as cooks and laundresses. Taken altogether, this composite army reflected the international nature of the British colonies in the 18th century. The Scottish Highlanders marched alongside the Germans of the Royal American Regiment. Throughout the ranks of the provincial troops one could find Swedes, Dutch, Finns, Poles, and Irish. One regimental chaplain was required to deliver two sermons on Sunday – one in English and the other in the Gaelic language of the Scots known as Erse.

While General Forbes occupied himself with contracting supplies and dealing with provincial authorities, the day-to-day operations of the army were handled by his second-in-command, Colonel Henry Bouquet, a Swiss mercenary commissioned in the Royal American Regiment. From the beginning of the campaign, Bouquet proved himself to be a competent and resourceful officer. He was a keen observer of wilderness warfare who wished to avoid the pitfalls that hampered Braddock’s command. As such, he advocated the use of tactics better suited for irregular combat against Indians. Joseph Shippen, an officer in the Pennsylvania Regiment, observed Bouquet drilling the troops during the campaign and wrote:

“Every afternoon he exercises his men in the woods and bushes in a particular manner of his own invention which will be of great service in an engagement with the Indians.”

A New Road

A Road Over the Mountains

While General Forbes remained behind to complete the organization of his army, Colonel Bouquet led the advance across Pennsylvania. Taking the road from Philadelphia, through Lancaster and on to the Susquehanna River, travel was uneventful since the line of communication into the interior had been developed some years before. Bouquet crossed the river at Harris Ferry (present-day Harrisburg) and continued on to Carlisle, which served as the forwarding point for men and supplies. At Carlisle, the colonel suffered his first disappointment when wagons needed to haul supplies westward, failed to arrive. The Pennsylvania farmers were reluctant to lease their transports to the army fearing they would not be paid. An angry Bouquet fired off a letter to the magistrates in Berks County demanding that the wagons be immediately forwarded to the frontier.

Departing Carlisle on June 5, Colonel Bouquet headed for Shippensburg, the last settlement in the west. The road became more difficult to negotiate and the colonel declared that the “sharp stones will very soon wear out the 3 pairs of shoes that each soldier is to have.” The Pennsylvania troops were sent forward to repair the highway and open the trail between Forts Loudon and Littleton, two provincial outposts to the west. This trail, which had first been cut by James Burd in 1755, ran up Path Valley and crossed over Tuscarora Mountain through a notch later known as Cowans Gap. At this point the going became increasingly difficult. Bouquet informed General Forbes:

“Of all the roads where it is possible for a wagon to go, this is the worst… It is of rock, partly solid, partly loose and sharp stones. The rains have carried away all the earth… Our wagons are breaking down; our horses are losing their shoes. It is a wretched state of affairs.”

Little did the colonel know that greater challenges would face him as he drove forward toward Fort Duquesne.

By June 28, Bouquet’s advance force reached a small trading village known as Raystown, named for the Indian trader John Wray who had trekked the western hills as early as 1732. It was here that Bouquet set about building a large compound named Fort Bedford. He then sent orders directing the troops from Maryland and the Virginia forces under the command of Colonel George Washington to cut a trail northward from Fort Cumberland. It was also at Fort Bedford that the question arose regarding which route the army should take to reach Fort Duquesne. Washington and the Virginians proposed that Forbes’ men drop south from Raystown to Cumberland and then use Braddock’s old road. Colonel Bouquet, on the other hand, favored cutting a new road directly across the Allegheny and Laurel Ridges, thereby saving nearly fifty miles while avoiding several treacherous river crossings. The question remained, however, was it possible to even build a new road over the mountains? Bouquet sent out several scouting parties who returned to inform him that, while difficult, it was indeed possible to secure a passage over the mountains. In the end, General Forbes sided with Bouquet and construction began on the new route.

While Henry Bouquet labored to get his advance force over the mountains, Forbes struggled in the rear to move forward the main army. The general was increasingly plagued with an intestinal disorder that left him prostrate for weeks at a time. He remained at Carlisle for more than a month until his symptoms subsided enough for him to resume the march. He arrived at Shippensburg on August 12 only to be struck down once again by his ailment. Throughout his ordeal, Forbes fretted that winter would arrive before he could reach his objective of seizing the French fort at the Forks of the Ohio.

Talks

A Message to the Indians

Forbes was also worried about the disposition of the Indians that had allied themselves with the French. As early as June, the general had written to a fellow officer that he proposed “to send a solemn message among the Delawares and Shawanese to beg a meeting with them where they choose to appoint, when I hope to persuade many of them at least to remain neutrals for this Campaign.” To deliver this “solemn message,” Pennsylvania authorities appointed Christian Frederick Post, a forty-eight-year-old Moravian missionary who spoke the Delaware language. Facing great hazards, Post crossed over the mountains in July to council with the Indian leaders living in the Ohio River Valley. He assured the chiefs that the British wanted to resume the peace and that, if the Indians abandoned their support of the French, they would guarantee to them their treasured homeland. Led by an influential Delaware peace advocate named Tamaqua, Post delivered his message to the assembled Indian leaders directly across the river from Fort Duquesne. The Indians informed the missionary that they were deeply concerned over the powerful army that inched ominously closer to their villages. They told Post:

“We have great reason to believe you intend to drive us away, and settle the country; or else why do you come to fight in the land that God has given us?”

The Moravian assured the Indian leaders that Forbes’ only purpose was to drive off the French. Satisfied, the chiefs told Post to return to the east and bring back “the great belt of peace to them and then the day will begin to shine clear over us. When we hear once more from you, and we join together, then the day will be still, and no wind, or storm, will come over us, to disturb us.” With that, Post returned over the mountains to retrieve the peace belt and a copy of the treaty assuring the Indians of British sincerity.

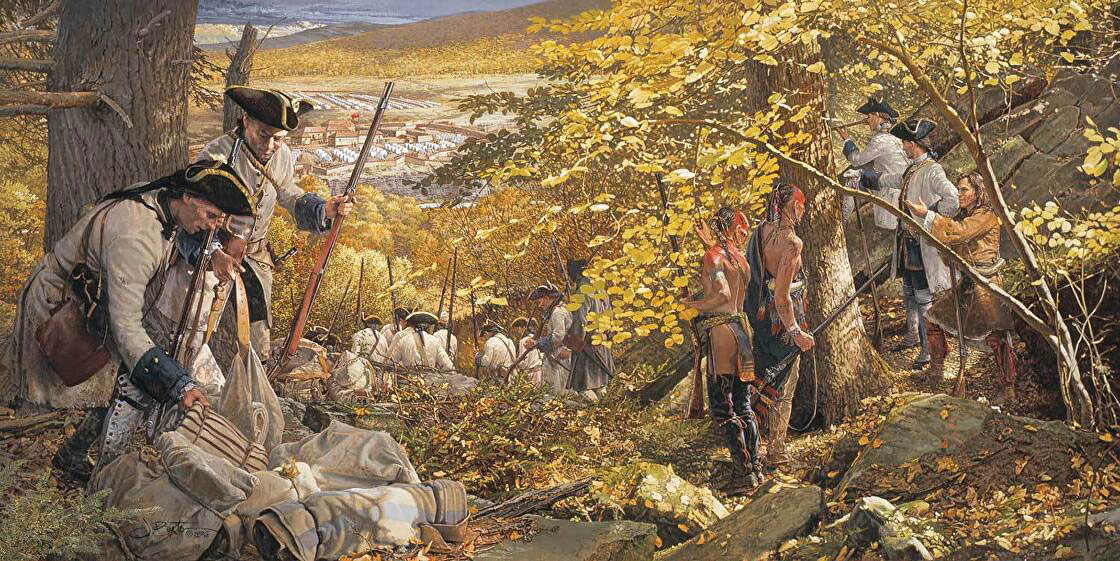

In the meantime, Colonel Bouquet continued to press forward, passing over the Laurel Ridge to arrive at Loyalhanna Creek on September 7. Here he met Colonel James Burd, commanding one of the Pennsylvania battalions, who had been sent forward to fortify the position. The outpost erected on the site was named Fort Ligonier in honor of General John Ligonier, a close advisor to William Pitt. General Forbes’ advance was now only a scant fifty miles from Fort Duquesne. From here, Bouquet felt confident enough to send out a reconnaissance force to harass the enemy at the confluence and bring back valuable intelligence. Unfortunately, this expedition, led by Major James Grant of the 77th Highland Regiment, was attacked and defeated by the French and Indians just beyond the walls of Fort Duquesne on September 14th. During the battle, Grant, who was himself captured, lost 300 men. A dejected Bouquet wrote to General Forbes, saying

“I shall add no reflection regarding this affair. They are too disagreeable.”

Despite the setback of Grant’s defeat, the spirit of the troops remained high. After a tortuous summer, struggling to reach the source of so much despair to the frontier settlers, the army was within striking distance of their objective. Throughout September and October, the camp at Loyalhanna swelled as Forbes’ main army began arriving. On October 12 a large party of French and Indians, numbering perhaps 600, made a surprise attack upon the fort but were repulsed after a sharp engagement lasting about three hours. Failing in their attack, the French returned to Fort Duquesne, likely resigned to the fact that the only thing that would stop the British juggernaut would be the advance of winter.

Finally, on November 2nd, General Forbes reached Fort Ligonier. He was pale and emaciated from the intestinal disease that wracked his body. During the journey from Fort Bedford, he had to be carried in a litter strung between two horses. With winter already making its presence known, the weakened general was now faced with the fateful decision to push forward to the Ohio, or to fall back and wait for the coming of spring. He convened a council of war with his officers who determined that “the risks being so obviously greater than the advantages, there is no doubt as to the sole course that prudence dictates,” in other words – wait until the following year.

Friendly-fire

A Tragic Mistake

The following evening a tragic event occurred that brought about a profound change in circumstances. Scouts came running into the fort to report that a French raiding party was lurking about. Lt. Col. George Mercer, at the head of a detachment of Virginians, sallied out to drive off the enemy. A sharp skirmish ensued and General Forbes ordered Colonel Washington to take another detachment of Virginia troops and support Mercer. As Washington and his men approached the scene in the darkness, Mercer’s forces mistook their fellow Virginians as a French reinforcement and opened fire. Believing they were under attack by the French, Washington’s men returned the fire. Suddenly realizing the tragic mistake, Colonel Washington ran between the two lines, knocking up the muzzles of the muskets with his sword and ordering the men to cease firing. By the time the gunfire stopped, fourteen Virginians had been killed.

One providential consequence of this friendly fire episode was that the Virginians had managed to capture three French soldiers. One of these prisoners turned out to be an English deserter who, upon interrogation, revealed that the enemy’s position at Fort Duquesne was desperate. According to this informant, the French were low on provisions and many of the soldiers had departed down the Ohio to winter quarters. In addition, the British were pleased to learn that Christian Frederick Post’s diplomatic efforts had succeeded in convincing the Indians to abandon their French allies. With this piece of intelligence, General Forbes determined to put his bedraggled army into motion and make the final push to seize Fort Duquesne.

Pittsburgh

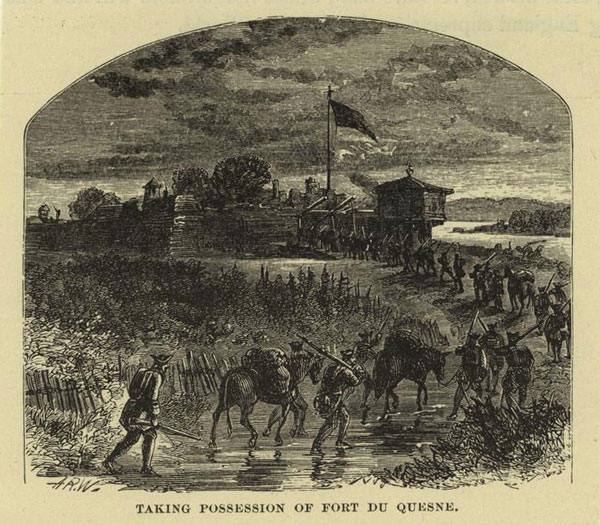

The Birth of Pittsburgh

By November 24, Forbes’ advance was only a day’s march from their objective. That night, Indian scouts arrived at the British camp to report seeing smoke coming from the direction of Fort Duquesne. The general sent forward a troop of cavalry to determine the truth of this intelligence. When they arrived at the confluence, the soldiers discovered that the French had destroyed everything they could not carry away and burned the fort to the ground. The following day, General Forbes was carried in his litter to the charred ruins where he penned a letter to William Pitt, saying, “I have used the freedom of giving your name to Fort Duquesne, as I hope it was in some measure the being actuated by your spirits that now makes us Masters of the Place.” He ended his message on a prophetic note, writing that:

“these dreary deserts will soon be the richest and most fertile of any possessed by the British in North America.”

Little did General Forbes realize that only part of his prophecy would become true. British victory over the French had been costly and the home government insisted that the provincials bear a greater burden in the maintenance of this newly won empire. In addition, officials in Great Britain determined to assume a more firm control over their distant colonial possessions. All of this would eventually lead to a spirit of revolutionary agitation among many of the veterans who had served in war. In the end, George Washington, who had fought so hard to win the Forks of the Ohio from the French, found that he had no other recourse but to resist what he considered Britain’s oppressive policies. Indeed, as General Forbes predicted, Pittsburgh grew to become a great metropolis – but not under British rule.

Bios

Biographies

John Armstrong (1717-1795)

Born in Ireland, John Armstrong settled in the backcountry of Pennsylvania with many other Irish and Scots-Irish immigrants. He was an accomplished surveyor and, when the Pennsylvania Regiment was finally created in the aftermath of Braddock’s defeat, Armstrong was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel, commanding one of the three battalions. Colonel Armstrong worked feverishly in the summer of 1756 to maintain a line of defense along the frontier against an increasing number of Indian raids. This defensive line proved ineffective, however, as the enemy would either bypass the loadstone forts erected to protect the backcountry, or elude the troops patrolling between those outposts. The Indians became so bold that summer as to attack one of these provincial stockades, Fort Granville. During this attack, Colonel Armstrong’s brother, Edward, was killed.

After the raid on Fort Granville, Armstrong recognized the futility of trying to maintain this defensive perimeter and proposed to Governor Robert Morris that a punitive strike be made against the raiders. His target was the Delaware village of Kittanning, located along the Allegheny River north of Fort Duquesne. With 300 men, Armstrong launched a surprise attack against the enemy stronghold on September 8, 1756. While there were few Indian warriors in the village at the time, the Pennsylvanians managed to kill a principal war leader named Captain Jacobs and destroy a great quantity of supplies. Fearful that the French or other nearby Indians might reinforce the enemy at Kittanning, Armstrong led a precipitous retreat from the battlefield in which a number of his men became separated from the main force. In all, the colonel lost nearly 30 men during the expedition.

During the Forbes Campaign, Armstrong and his Pennsylvanians provided valuable service in building fortifications, clearing trails, and garrisoning outposts along the line of communication. Bouquet regarded the colonel as “a man of Publick Spirit, and Zealous for the Good Services, and the Prosperity of his Country.” According to one account, it was John Armstrong who was given the honor to raise the Union Jack over the ruins of Fort Duquesne at the end of the campaign.

Armstrong remained in the military after the French and Indian War and rose to the rank of brigadier general in the Continental Army during the American Revolution. Retiring from the army due to poor health, he was elected to Congress and served as a delegate from 1778 until 1780. He was returned to Congress in 1787 and served for two more years. He then returned to Carlisle where he served as one of the first trustees of Dickinson College. He died in 1795 and is buried in the Old Carlisle Cemetery.

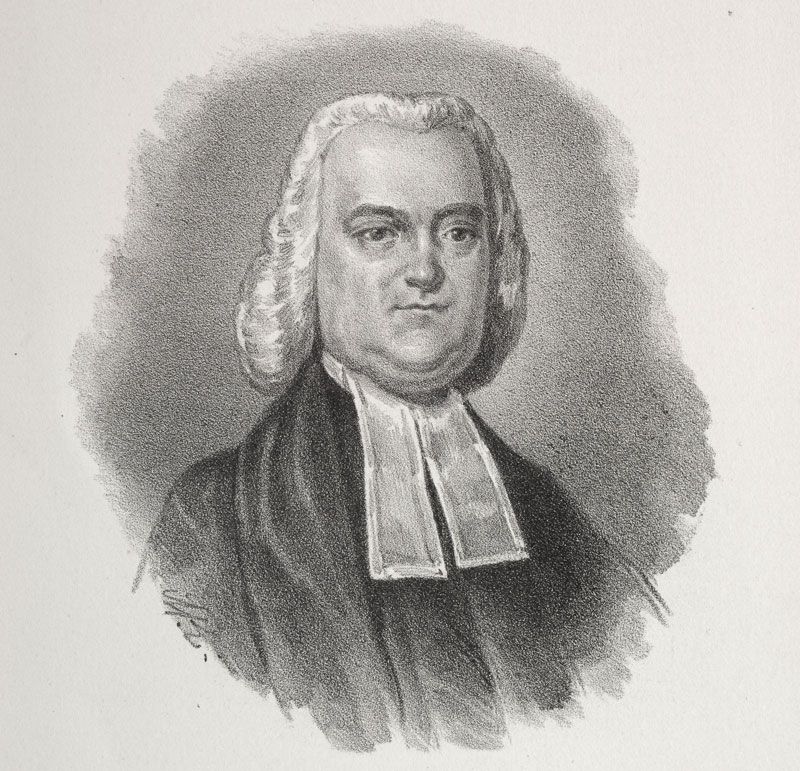

Rev. Thomas Barton (1730-1780)

Aside from the official military papers of Bouquet and Forbes, perhaps the best account of the campaign to seize Fort Duquesne came from a journal kept by Thomas Barton who served as a chaplain to the army. Born in Ireland in 1730, Barton came to Pennsylvania in 1753. Under authority from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, he was sent to the lands west of the Susquehanna River where he served as the pastor for Anglican congregations in Huntington, York and Carlisle. When the Indian raids began in the fall of 1755, Barton was quick to report on the defenseless state of the frontier. In a letter to the provincial secretary, Richard Peters, the minister confided, “Not a Man in Ten is able to purchase a Gun. Not a House in Twenty has a door with either Lock or Bolt to it.” To help defend his frontier congregation, Barton put down his Bible and picked up a musket, serving as a captain in one of the hastily organized militia companies.

When the Forbes Campaign was being organized, it seemed logical to appoint Barton as chaplain to the Pennsylvania Regiment. Many of these men were Scots-Irish, however, and preferred to have a Presbyterian minister serve as their spiritual guide. Consequently, General Forbes offered Barton a post as chaplain for the soldiers belonging to the “Communion of the Church of England.

Throughout the expedition, Barton kept a journal that provides historians with a vivid and colorful account of important events, places and activities. His descriptions of the frontier outposts along the trail are particularly illuminating. Upon reaching Shippensburg he noticed that Fort Morris was “A trifling Piece of Work with 4 Bastions, & about 120 feet square.” He was equally unimpressed with Fort Loudoun, calling it “a poor Piece of Work, irregularly built, & badly situated at the bottom of a Hill Subject to Damp & noxious Vapours. It has something like Bastions supported by Props, which if an Enemy should cut away, down tumbles Men & all.” Barton found Fort Lyttelton to be a better defensive outpost with “a regular & well-plan’d Square Stockade of 126 feet. The Situation pleasant & advantagious.”

During his tenure as chaplain, Barton had the misfortune of ministering to Private John Doyle, a deserter from the Pennsylvania Regiment, who had been apprehended, court-martialed, and sentenced to death. Barton walked with the condemned man to the place of execution where Doyle gave a brief speech admonishing his fellow soldiers “To live sober Lives; to beware of bad Company; to shun pretended Friends, & and loose wicked Companions.” Barton then recorded that the firing squad advanced so near Doyle “that the Muzzles of their Guns were within a Foot of his Body. Upon a Signal from the Serjeant Major they fir’d, but shot so low that his Bowels fell out, his Shirt & Breeches were all on Fire, & he tumbled upon his Side; rais’d one Arm 2 or 3 times, & soon expir’d.” Barton called the execution, “A shocking Spectable to all around him; & a striking Example to his Fellow Soldiers.”

Unfortunately, Barton’s lively journal entries abruptly ended on September 26th, the day John Doyle was executed. Perhaps the pastor found military discipline so harsh that he lost his admiration for army life.

After the Forbes Campaign, Barton returned to his various congregations where he served as a pastor until 1760. During the American Revolution, he refused to take an oath of allegiance to the new United States government and left Pennsylvania with his family. After Barton’s death in 1780, his journal passed through family hands until 1970 when it was purchased at an estate auction by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The following year, William Hunter, transcribed and edited the aged artifact and published it in the society’s journal, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 95 (October 1971).

Henry Bouquet (1719-1765)

Born near the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland, Henry Bouquet seemed well suited for army life. At the young age of 17 he joined a Swiss regiment pledged to fight for the Dutch. During the European conflict known as the War for the Austrian Succession (1744-48) he served in another Swiss unit recruited to fight for Sardinia. Afterward he re-entered Dutch service as a lieutenant colonel. While stationed at the Hague, Bouquet became acquainted with Sir Joseph Yorke, the British ambassador. Due to the high cost of transporting British troops by ship to fight in America during the French and Indian War, British officials decided to save money and recruit among the Protestant German population already living in the colonies. To lead these troops, talented and experienced officers who spoke the language were needed. Consequently, Yorke offered Bouquet a commission as a lieutenant colonel in a unit that came to be known as the 60th Regiment of Foot; or, more commonly, the Royal American Regiment.Colonel Bouquet arrived in the colonies in 1756 and set about proving himself as a capable and energetic officer. Senior commanders sought his advice in the placement and construction of fortifications. He even drafted a detailed plan for a campaign that became the basis for General Forbes’ expedition against Fort Duquesne.

Bouquet represented himself as a cultured and refined officer-gentleman. He was fluent in German, French, and English, and his wardrobes boasted several scarlet coats with broad gold lace. He was welcomed into the homes of Philadelphia’s elite. Yet, despite such outward appearances, he developed into a rugged and trusty frontier soldier with an incisive understanding of wilderness warfare as practiced by the Indians and French irregulars. General Forbes found him to be indispensable during the campaign and relied solely upon Bouquet’s talent and skill to move the army forward toward its objective.

After the end of the Forbes Campaign, Colonel Bouquet remained in Pennsylvania and later played a crucial role in bringing about an end to the Indian conflict known as Pontiac’s Uprising. His victory over the warring tribes at the Battle of Bushy Run in 1763 brought relief to a besieged Fort Pitt and compelled the enemy to retreat deeper into the Ohio Country. The following year he led an army to the Muskingum River where he forced the Indians to capitulate and give up many of their captives.

In 1765 the British army amended its policy of not allowing foreign-born officers to serve as generals, and promoted Bouquet to brigadier. He was assigned to command the Southern District with his headquarters at Pensacola, Florida. Upon arrival at his new post, however, Bouquet immediately fell ill with yellow fever and died on September 2, 1765. When news of his sudden death reached Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania Gazette commented that “His superior judgment and knowledge of military matters, his experienced abilities, known humanity, remarkable politeness and constant attention to the civil rights of his Majesty’s subjects, rendered him an honor to his country.”

James Burd (1726-1793)

A descendent of the famous warrior-king Robert the Bruce, James Burd came to Philadelphia in 1747. He established himself as a merchant and married Sarah Shippen, daughter of the former mayor of the city. By 1752, Burd had moved to the frontier community of Shippensburg where he worked for his father-in-law. During the Braddock campaign in 1755, Burd worked to secure flour and other supplies for the troops. Pennsylvania Governor Robert Morris appointed Burd as one of the commissioners to survey and construct a road that would connect Pennsylvania’s frontier communities with Braddock’s line of march. This was intended to facilitate the transportation of wagons and supplies to the army. Burd’s road came within fifteen miles of intersecting with Braddock’s trail when word arrived of the general’s defeat and death. Later, General Forbes would use portions of Burd’s old route as he marched toward Fort Duquesne.When the Pennsylvania Provincial Regiment was formed in 1756, Burd joined the army and was eventually commissioned as a major in the Third Battalion and assigned the task of building fortifications to protect the frontier. By the end of the year, he found himself in command of Fort Augusta, near present-day Sunbury, Pennsylvania. For the next eighteen months, Burd kept the line of communication open from the fort to Lancaster, sent out patrols to scour the woods and mountain passes for Indian raiding parties, and kept his men supplied and equipped.

When the Forbes expedition began, Burd, who now commanded the Third Battalion with the rank of colonel, proved to be indispensable. In a letter to Forbes, Henry Bouquet wrote “I cannot let Col. Burd go. He is a very industrious man, who is very necessary to me.” As such, Burd and his men were usually in the vanguard of the army as it advanced toward Fort Duquesne.

Following the Forbes Campaign, Burd remained in command of the Third Battalion and supervised the completion of his old road to the Monongahela River. Here, near the mouth of Redstone Creek, he built Fort Burd. Although this outpost was quite small, it served as an important defense point and supply depot through the American Revolution.

In 1766, Burd moved his wife and six children to present-day Middletown, located along the Susquehanna. Here he built a spatial stone mansion named Tinian. He continued to be active in politics and military affairs, and served as a local magistrate and justice of the peace. While he supported the revolutionary cause, he did not take an active role in the war due to a dispute over his military rank. He died in 1793.

John Forbes (1707-1759)

Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, John Forbes was the son of a soldier who also served as the laird (the Scottish word for lord or landowner) over Pittencrief, an estate that in later years was owned by the industrialist Andrew Carnegie. After abandoning a career in medicine, young John decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and, in 1735, purchased a commission as an officer in the Royal North British Dragoons, better known as the Scots Greys. Ten years later, Forbes found himself fighting in his native Scotland to suppress the Jacobites who were intent upon placing Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie) upon the throne. During the famous Battle of Culloden, which finally crushed the rebellion, he barely escaped death when a bullet struck a farthing coin in his breast pocket.Recognized as a faithful and talented officer, Forbes rose in rank while serving on the staffs of such illustrious generals as the Duke of Bedford, Lord Ligonier, and the Duke of Cumberland. While British politicians wrangled over military policy in the summer of 1757, John Forbes came to America to serve as the adjutant general for Lord Loudoun. When Pitt and Ligonier began to plan their new strategy for victory over the French, both men sought dependable officers to carry out those measures. Consequently, in December 1757, Forbes was promoted to brigadier general and eventually assigned the task of clearing the French from the Ohio Country.

Even before arriving in Philadelphia to take command of the expedition against Fort Duquesne, the general suffered from some mysterious illness. He complained to Lord Loudoun of swelling in his limbs and concluded that “there must be some devilry in this Air, that has such ane effect upon me.” Ignoring his infirmities, Forbes plunged into the monumental chore of assembling and equipping his army. After ten weeks of preparation, the general finally departed from Philadelphia to catch up with the lead elements of his army that had already reached Raestown, far to the west. After reaching Carlisle, the general was again stuck down by a severe intestinal illness that left him “as weak as a new born Infant.” As the campaign progressed, Forbes’ condition increasingly worsened and he was forced to be transported in a litter slung between two pack horses. At the successful conclusion of the expedition, the general immediately made the painful trip back to Philadelphia where he died on March 11, 1759, at the age of 51. He was buried in Christ Church.

Mary Jemison (1743-1833)

Thomas Jemison was like thousands of other immigrants who came to America in the 18th century. His dreams were to acquire land, raise his family, and free himself from the grinding poverty, civil unrest, and persecution that was so commonplace in Europe. Like so many other immigrants, he took his family deep into the rugged wilderness of Pennsylvania where he cleared land and established “a large farm, and for seven or eight years enjoyed the fruits of his industry.” Then, on April 5, 1758, just as John Forbes was preparing to depart from New York to begin his campaign, a raiding party of Shawnees and French swooped down on the Jemison homestead. During the attack a neighbor was killed and Thomas, his wife, and four children were taken into captivity, along with another woman and her three children. Two of Jemison’s sons, Thomas, Jr. and John, escaped by hiding in the barn.With their captives in tow, the Indians and their French allies headed back toward Fort Duquesne. That night, the Indians killed all of their hostages except Thomas’s fifteen-year-old daughter, Mary, and another neighbor boy. Arriving at the fort, the captors separated the prisoners and Mary was given over to two Shawnee women to replace the life of their brother who had been killed the year before. From that point on, she later recalled, “I was ever considered by them as a real sister, the same as though I had been born of their mother.”

Mary Jemison remained with the Indians the rest of her life. She first married a Delaware named Sheninjee and had two children, although her first child died soon after birth. She later married a Seneca chief called Hiokatoo and had six more children. Mary had many opportunities to return to the white world, but she chose to remain with her Indian family. As she later related, “With them was my home; my family was there, and there I had many friends to whom I was warmly attached in consideration of the favors, affection and friendship with which they had uniformly treated me, from the time of my adoption.” She died on the Buffalo Creek Reservation in New York in 1833. Many descendants of Mary Jemison continue to live among the New York Senecas today.

Robert Kirkwood

While historians are fortunate to have numerous accounts of the French and Indian War coming from military officers, seldom do they have available the recollections of the common soldier in the ranks. One important exception is the memoirs left by Robert Kirkwood, a Scotsman who served in both the 77th Regiment of Foot (Montgomery’s Highlanders) and the 42nd Regiment (better known as the Black Watch). Not only do Kirkwood’s reminiscences provide researchers with a candid look at the life and experiences of an enlisted man, but they also detail some of the most dramatic incidents during the Seven Years’ War in America.Robert Kirkwood was born in Ayrshire, Scotland, and worked as a cooper before enlisting in the 77th Regiment of Foot in 1756. After a nine-week voyage, the Highlanders landed in Charleston, South Carolina, where they “lay in the Barracks there for nine months” before being ordered to Pennsylvania to embark upon the Forbes Campaign. On the march across the desolate frontier, Private Kirkwood could not help but notice “the horrible situation of this beautiful country, at that time. The Houses deserted, the Corn fields, Orchards, and well-filled Haggards yet smoking, melancholy proofs of the barbarous enmity of the merciless Indians.”

It was Kirkwood’s misfortune to be part of Major James Grant’s disastrous attack on Fort Duquesne in September 1758. “It is impossible to describe the confusion and horror which ensued,” he recalled of the battle, “when all hopes of victory was gone.” When the vanquished Highlanders finally broke and ran, Kirkwood was shot in the leg by pursuing Indians. “I was immediately taken,” the Scotsman remembered, “but the Indian who laid hold of me would not allow the rest to scalp me, tho’ they proposed to do so; in short he befriended me greatly.” The Shawnee warrior who captured the private decided to adopt him to replace the life of a brother who had been killed earlier during a battle with the Cherokees. Altogether, Kirkwood spent eight months living with the Indians before he managed to escape. After a harrowing journey through the wilderness that lasted 22 days, he finally made it to the safety of Fort Cumberland, Maryland.

Kirkwood rejoined his regiment in July 1759, just in time to embark upon General Jeffrey Amherst’s expedition against the French at Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point. Once the British had succeeded in seizing these strategic outposts, Kirkwood volunteered to accompany the famous partisan ranger, Major Robert Rogers, on his raid against the Abenakis Indian village known as St. Francis. He later remembered the attack on the town as “the bloodiest scene in all America.”

After the fall of the French stronghold at Montreal in autumn of 1760, Kirkwood once again joined Rogers’ Rangers on a expedition to take control of Fort Detroit. Following this adventure, he claimed to have participated with his regiment on a campaign against Martinique; but, in reality, Kirkwood deserted from his regiment. He was later apprehended and placed in the guardhouse at Fort Ontario, near Oswego, New York. He remained a prisoner until pardoned by General Amherst in August 1762.

In the summer of 1763 remnants of the 77th and 42nd Highland Regiments were ordered back to Pennsylvania to participate in Colonel Henry Bouquet’s relief expedition to Fort Pitt which was under siege during Pontiac’s Uprising. Consequently, Kirkwood took part in the Battle of Bushy Run. His recollections of the Highland charge that secured victory for the British evoke of the drama of the scene. “We met them [the Indians] with our fire first,” he remembered, “and then made terrible havock amongst them with our fixt bayonets and continuing to push them every where. They set to their heels and were never after able to rally again.”

Robert Kirkwood remained in America until 1767 when his regiment returned to Great Britain. Sometime afterward he retired from the army and, in 1775, published his memoirs. Unfortunately, he then slipped into obscurity. The only known original copy of his amazing recollections is housed in the British Library in London.

Francois-Marie Le Marchand de Lignery (1703-1759)

Marchand de Lignery entered military service at the age of 14 as a cadet in the French colonial forces. He gained considerable experience in frontier warfare fighting Indians while serving under his father who commanded French forces in the Illinois Country. By the end of King George’s War in 1748, Lignery had participated in 12 separate campaigns, including attacks against British forces in Acadia and Nova Scotia. Three years later he was promoted to captain.In 1755, Lignery accompanied a party of French soldiers escorting Indian allies to Fort Duquesne. He took part in Braddock’s defeat that summer and was awarded the Cross of Saint Louis for distinguished service during the battle. Eight months later, the captain was placed in command of all French forces on the Ohio with orders to cultivate good relations with the neighboring Indians and to keep the British at bay by sending raiding parties against the frontier communities. His efforts were successful in pushing back Anglo-American settlement in Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.

As the tide of war began to turn against the French in 1758, Lignery made a valiant effort to hold on to the strategic Forks of the Ohio. After the attack against the British encampment at Loyalhanna in mid-October, the captain hoped that the British would halt their advance toward his position until the following spring. With supplies running low, Lignery had no choice but to reduce his garrison at the fort and send most of men to winter quarters down the Ohio River. This action left him with only 300 soldiers and less than 200 remaining Indian allies. Nonetheless, in early November, the captain made one last attempt to stop Forbes’ progress by sending a small detachment to Loyalhanna to harass the enemy. It was during this sortie that the British managed to take several prisoners, one of whom revealed the weakened condition of Lignery’s garrison. With this intelligence, Forbes decided to move forward.

After destroying Fort Duquesne, Lignery headed north to winter quarters at Fort Machault, located at the confluence of French Creek and the Allegheny River. Throughout the spring and early summer of 1759, the captain gathered reinforcements amounting to more than 1,100 French and Indians to be used in a counterattack against the redcoats who were now in possession of the Forks of the Ohio.

Just before departing down the river to attack the vulnerable British position, Lignery received orders to head north in an attempt to relieve the garrison at Fort Niagara that was under siege by a combined force of redcoats, New York Provincials and Indians led by Sir William Johnson. Lignery’s relief force arrived at Niagara on July 24, but the Indians refused to join the French in their attempt to break through the British lines. Undaunted, the captain led his men forward into the face of enemy fire. British volley fire cut the French to pieces and Lignery was struck by a musket ball in the thigh. The wound proved to be fatal and the captain died at Fort Niagara while being held as a prisoner of the British.

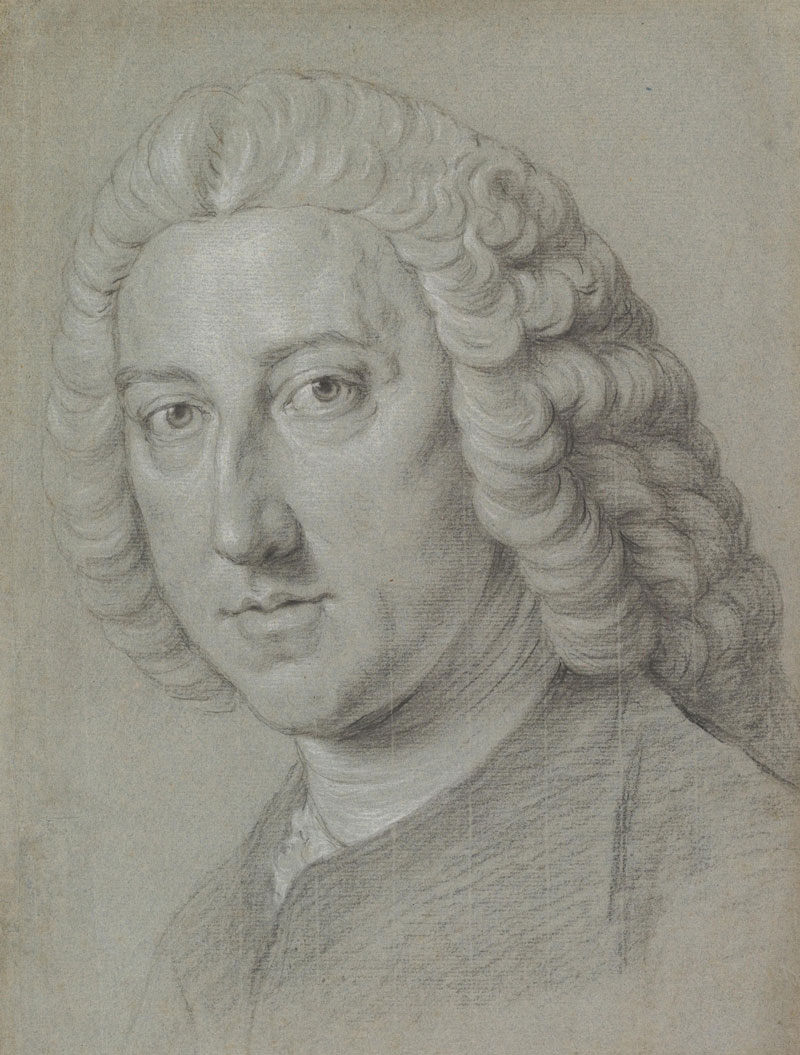

William Pitt (1708-1778)

The person most responsible for John Forbes’ campaign against Fort Duquesne was Great Britain’s Secretary of State, William Pitt. Born at Westminster in 1708, Pitt came from a family of considerable wealth and political influence. After attending school at Eton, he entered Trinity College, Oxford in 1727; however, due to chronic bouts of gout that plagued him throughout his life, he was forced to withdraw from the institution. At the age of 27, Pitt became a member of the House of Commons where he was greatly admired by the public due to his opposition of many government policies.By 1756, with the war against France going badly in both Europe and North America, King George II had little choice but to elevate the popular Pitt to the position of Secretary of State of the Southern Department. In this role, he continued to argue over war policy with the king’s favorite ministers. Further setbacks in the struggle against France eventually led Pitt to assume control over all military affairs. With his chief adviser, Sir John Ligonier, the secretary formulated a new strategy to win the war that relied upon Britain using its powerful navy to blockade French ports around the world. In addition, Pitt called for a new, three-pronged offensive in North America. This plan sent General Jeffery Amherst to seize the French stronghold at Louisbourg located near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, while General James Abercromby marched from Albany to attack the enemy garrison at Ticonderoga. The last element of Pitt’s plan called for General Forbes to defeat the French at Fort Duquesne.

After the fall of Canada in 1760 and the death of King George the following year, Secretary Pitt fell out of favor with the new monarch, George III. He resigned his position in 1761 after arguing for a continued aggressive war policy. Five years later, Pitt was recalled by the king to form a new cabinet of ministers. Broken in spirit and health, however, Pitt seemed to have little influence in directing policy related to the growing rift between Great Britain and its colonies in North America. He resigned his post as Prime Minister in 1768 and died ten years later at the age of 70.

Christian Frederick Post (1710-1785)

Perhaps no man was better qualified to carry General Forbes’ peace message to the Indians than Christian Frederick Post. Born in Prussia, he came to America in 1742 to take up missionary work among the Indians on behalf of the United Brethren, a religious sect generally known as the Moravians. He first worked among the Mahicans and Wampanoags in New York and Connecticut before moving to Pennsylvania to serve as a missionary to the Delawares. He married successively two Delaware women and understood and spoke their language. A contemporary Quaker named Charles Thomason remembered Post as “a plain, honest, religiously disposed man,” and a fellow missionary called him a “man of undaunted courage and enterprising spirit.”Following the Forbes Campaign, Post worked hard to maintain the peace that he had helped establish. Unfortunately, it was impossible to keep the whites from settling on Indian land in the Ohio Country. With an impending Indian war on the horizon again in 1762, Post traveled to Delaware villages located on the Tuscarawas River in eastern Ohio in an attempt to convince the Indians to remain at peace. With so many broken promises, however, the warriors were in no mood to listen to the missionary’s sermons and entreaties. Instead, they had found a new prophet named Neolin who told them of a “vision of Heaven where there was no White people but all Indians.”

Seeing that his efforts to maintain peace and convert the Indians to Christianity had failed, Post set off for the Carolinas in 1763 to preach among the Cherokees. The following year, he sailed for Honduras and Nicaragua to establish a mission among the Indians of the Mosquito Coast. He returned to Pennsylvania in 1767 to obtain additional financial support for his mission from the Moravians but was informed that his services were no longer needed. Undaunted, Post returned to Nicaragua to continue his efforts under the auspices of the Anglican Church. He finally came back to Pennsylvania in 1784 and settled in Germantown where he died the following year.

Sir John St. Clair (?-1767)

The responsibility for disbursing funds to pay for supplies, and insuring that food, ammunition, tents, clothing, and shoes made it to the troops in the field fell to Sir John St. Clair, a lieutenant colonel in the Royal American Regiment and the Quartermaster General of Forbes’ army. After fighting in the War for the Austrian Succession, Sir John came to America to serve as General Braddock’s quartermaster general. He was well-known for his arrogance and disdain for provincials, but proved to be an energetic and courageous officer. During the campaign, Sir John was always at the front directing the road building and hurrying supplies to the soldiers. At the Battle of Monongahela, St. Clair rode forward as the first shots rang out and was promptly wounded by a bullet in the chest. With blood flowing profusely from his wound, Sir John made his way back to General Braddock, imploring him, “for God Sake to gain the rising ground on [the] Right to prevent… being Totally surrounded.”After recovering from his wound, St. Clair once again proved to be an indefatigable if somewhat eccentric officer during the Forbes Campaign. He was known for his whimsical appearance and one soldier later commented that Sir John, “was somewhat grotesque, a long beard, blanket coat, and trousers to the ground. But he gave so good an account of what he went about, that I could have kissed him, and freely forgave his oddities.”

After the war with France had concluded, St. Clair chose to remain in America where he became a gentleman farmer in New Jersey. He died in 1767.

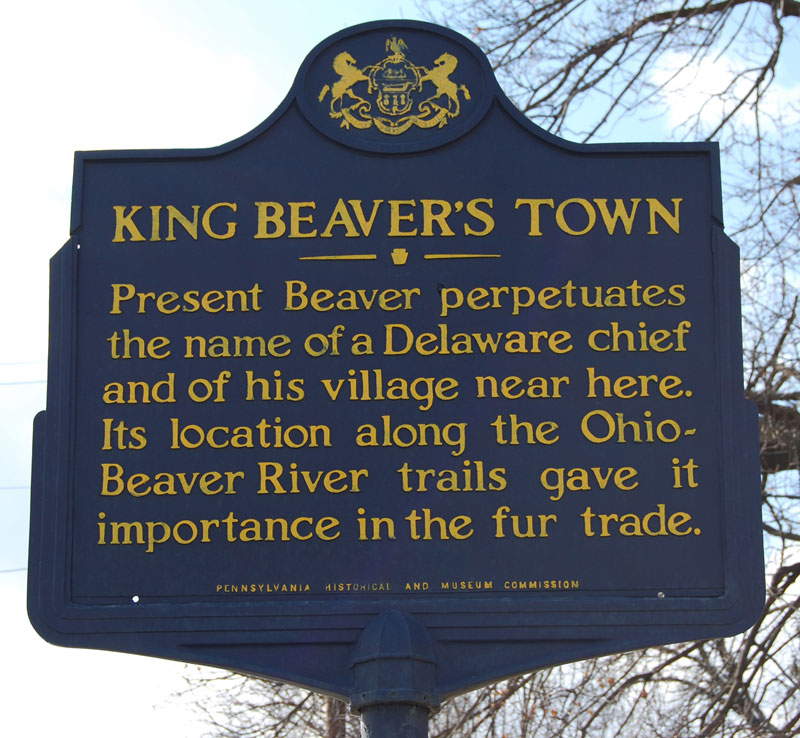

Tamaqua (?-1771)

Tamaqua, known to the British as King Beaver, came from the Schuylkill River region of eastern Pennsylvania. He was a member of the Turkey Clan and a nephew of the great Delaware leader Sassoonan. When Sassoonan died in 1747, Tamaqua and his two brothers, Pisquetomen and Shingas, assumed important leadership roles. While Shingas earned a reputation as a fearsome war captain, Tamaqua became equally influential as a diplomat among the Delawares.The growing rivalry between the French and British was alarming to Tamaqua and he feared that the various Indian nations residing in the Ohio Country would eventually be drawn into the conflict. In 1754, following George Washington’s defeat at Fort Necessity, Tamaqua warned the influential Seneca leader, Tanaghrisson, of the imminent crisis. He said, “You [the Iroquois] told us that You took Us under your Protection, and that We must not meddle with Wars…. We have hitherto followed your directions and lived very easy under your Protection, and no high Wind did blow to make Us uneasy; but now Things seem to take another turn, and a high Wind is rising.”

Known as a peace advocate, there is little evidence that Tamaqua took part in the Indian raids that devastated Pennsylvania in the years following Braddock’s defeat. Perhaps this is why Christian Frederick Post first came to King Beaver’s village at Kuskuski when he set out upon his peace mission in the summer of 1758. Post reasoned that if he could win over Tamaqua, then the chief would convince the other Indians to join in the armistice.

Immediately following the destruction of Fort Duquesne, King Beaver and other Indian leaders had a conference with Colonel Bouquet. At this meeting, Tamaqua told the colonel that since “our uncles [the Iroquois] have made peace with you, the English, and many other nations, so we likewise join and accept of the peace offered to us; and we have already answered by your messenger [Post], what we have to say to the General, that he should go back over the mountains; we have nothing to say to the contrary.”

Needless to say, the British did not withdraw as promised, but instead augmented their presence in the region by building Fort Pitt. This, in turn, contributed to the Ohio Country Indians joining in Pontiac’s Uprising in 1763. Once again, Tamaqua worked to restore the peace by encouraging other tribes to give up the prisoners they had taken during the conflict. In the years following, King Beaver’s name appears many times in documents relating to treaties and conferences held between the British and the Indians.

In his later life, Tamaqua once again came under the influence of the Moravians and invited them to establish missions among the Delawares in eastern Ohio. He converted to Christianity shortly before his death in 1771.